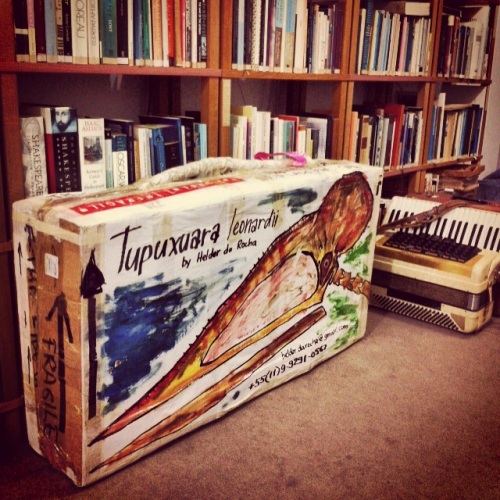

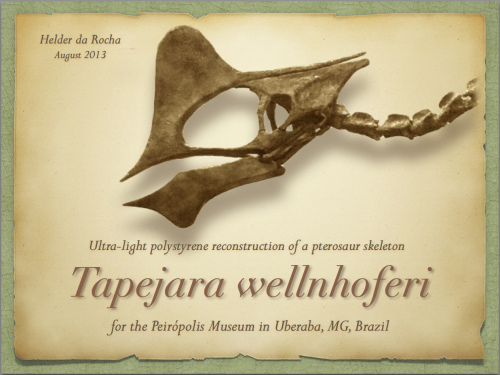

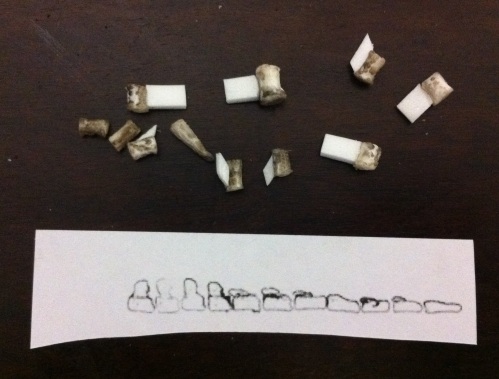

This weekend I traveled to Uberaba, MG, Brazil, where I installed this replica of a Tapejara wellnhoferi. I traveled with more than 190 individual unassembled bones. Arriving there I had three days and a half to put them together and assemble a Tapejara wellnhoferi pterosaur in a flying position. All the 196 bones are in this 16×23 cm box.

The skeleton was installed in a museum which is part of a cultural and scientific complex in the town of Peirópolis. It will be displayed in one of the museums in the complex.

Peirópolis is a small town located 20 km away from the city of Uberaba (pop. 300 000) in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. The whole area is situated over a geological formation from the late Cretaceous and contains several paleontological sites where hundreds of fossils, mostly reptiles, were found. The Peiropolis Dinosaur Museum (Museu de Dinosauros) is part of a scientific and cultural complex (Complexo Cultural e Científico de Peirópolis – CCCP) which also includes a research center (Centro de Pesquisas Paleontológicas Llewellyn Ivor Price) and another smaller museum installed in an old train station. The complex is administered by the Federal University of Triângulo Mineiro (UFTM).

The smaller museum contains only species which were found locally; another contains replicas and fossils from other parts of the country. This Tapejara is the first pterosaur that will be on display in the complex.

Besides installing the Tapejara, I also gave a small workshop showing how I researched, planned and created the individual bones from sheets of foam, demonstrating the techniques and materials used. In the end, I recycled a small tray by cutting two pieces to make a Tapejara humerus.

Assembly took me 3 and 1/2 days. It took long because I used silicone rubber to attach the bones together and its only completely dry in 24 hours (before that it gets gradually stronger, but it may tear easily.) I also used part of the first day to photograph each of the bones and weigh them. The whole collection weighs only 300 grams!

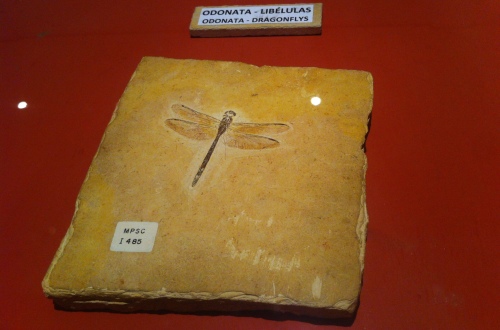

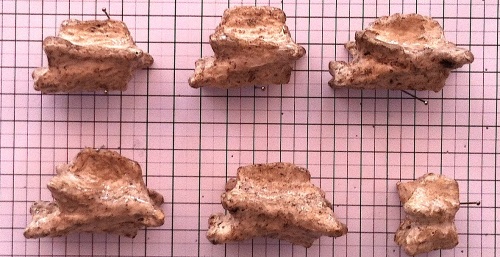

But before turning those bones into a Tapejara, I decided to turn them into a fossil first. This is a representation of the limestone slab which contains one of the most complete specimens: SMNK PAL 1137 (see “Eck et al, 2011, On the osteology of Tapejara wellnhoferi …”). The actual slab contains bones from three individuals, but I only have one so there are some bones missing. Anyway, here is SMNK PAL 1137 assembled with replicas of bones from one Tapejara:

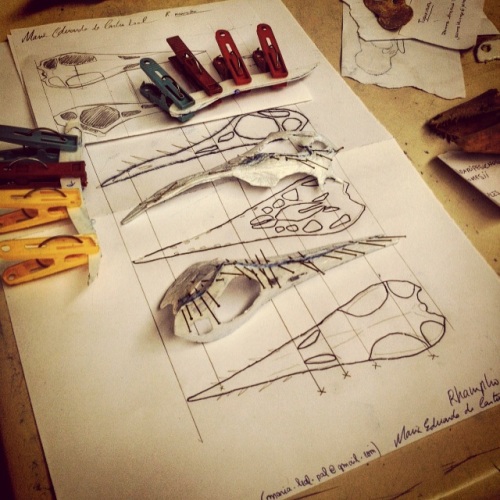

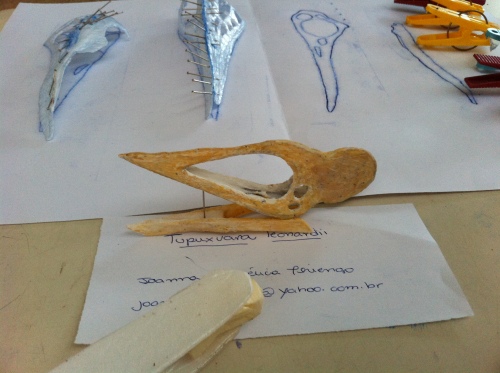

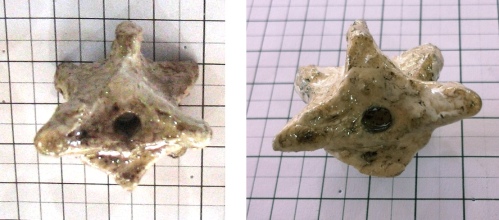

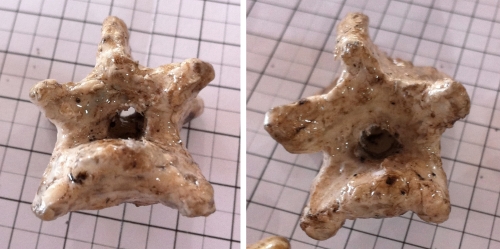

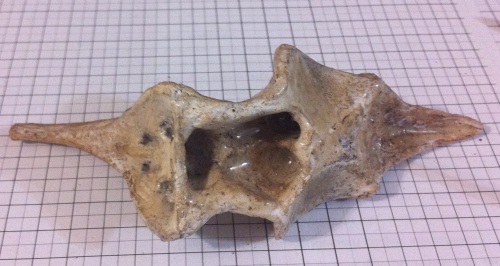

I started with the head (I used some of these pictures to illustrate the previous post). The neurocranium is attached dorsally to the upper crest (with silicone rubber “cartilage”, but shown below with pins) and at the anterior part of the orbits through the lacrimal bone (shown detached in the next two pictures, and attached with silicone rubber and two pins in the third).

The spine has a long rubber tube acting as a medulla. Here is the Tapejara with an assembled skull and spine (cervicals, dorsals, sacrum and tail). The quadrate bones, that articulate with the jaw, are shown below beside the skull and were not attached yet.

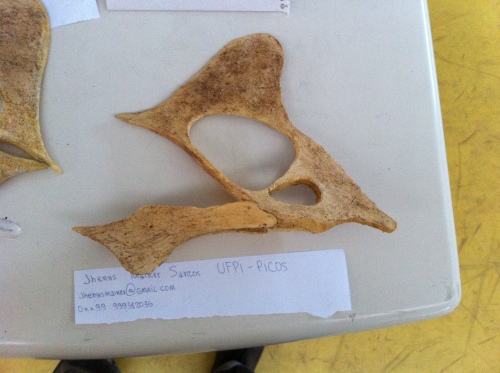

The next step is the assembly of the pelvis. Each bone was attached with silicone rubber, keeping it firmly in place while allowing some elasticity between the bones. Silicone rubber acts like cartilage. Below are some photos of the complete pelvis showing the sacrum, gastralia, pre-pubis, pubis, ischium and ilium (preacetabular and postsacetabular processes).

I was hosted by friends in Uberaba, and hanged the skeleton every night in my bedroom window. This is my window after the first day.

On Saturday I returned to the museum and assembled the feet, legs, part of the wings and part of the pectoral girdle. Here’s a pair of Tapejara feet. The bones are firmly attached but they retain some flexibility. You can pass your fingers between Tapejara’s toes.

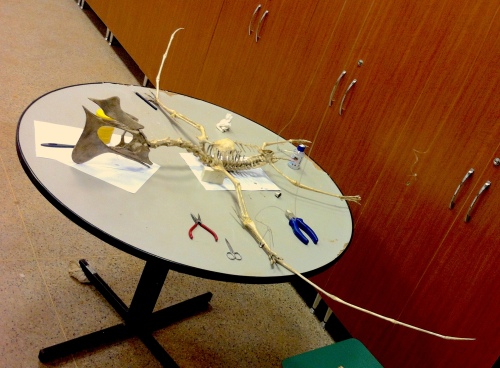

My table of bones.

Here are some views of the skull after I attached the mandible. The pins are holding it closed because I only added silicone rubber to the joints. When the silicone dries, the weight of the lower jaw should keep the mouth slightly open.

It’s easier to work on the ribs by hanging the skeleton. I attached practically all the ribs and the sternum (through four pairs of sternal ribs).

And this is my window after day 2.

On day 3 I occupied the kitchen at my friends’ place, and finally finished the pectoral girdle, connecting the vertebral ribs to the sternal ribs, and to the sternum and gastralia.

I didn’t use cartilagenous connections from the posterior vertebral ribs to the gastralia, nor did I leave them floating in the air. I used thin sternal ribs as placeholders since I had some spare ones. My intention was to remove them later, when the abdomen had dried and was strong enough, and replace them with pure cartilage to connect to the gastralia, but I forgot to do so. It’s not completely inaccurate the way it is (no fossil evidence against it – but perhaps the “floating ribs” should be smaller). Anyway, I can consider fixing that when I return to Uberaba and have an opportunity to review the replica.

Here is a view from the front showing the scapulocoracoid.

The limbs are almost done. This photo was taken just before connecting the carpals and fingers.

Oh, and this is Samuel – a Felis catus. He is always with me in the kitchen observing the Tapejara wellnhoferi. It probably looks like a big tasty bird for him.

Here is the finished Tapejara body. As you can see I used “sternal” ribs to connect gastralia (the last three ribs) to the vertebral ribs.

There is not enough space on this table for a pterosaur.

Almost done. Now some fingers.

A pterosaur hand. That long fourth dactylus is the pterus 🙂

And this is the end of day 3. All the small parts assembled into larger ones. I arrived in town with 196 parts, now I have six parts hanging in my window. I couldn’t assemble it all because it woundn’t fit in the car.

Monday morning. Tapejara for breakfast.

This is my host Regis. He is a musician and plays the guitar in a heavy metal band. This time, instead of a guitar, he holds a Tapejara. And the cat on the couch is one of the daughters of Samuel the cat.

Samuel was watching the skeleton on the kitchen table a while ago.

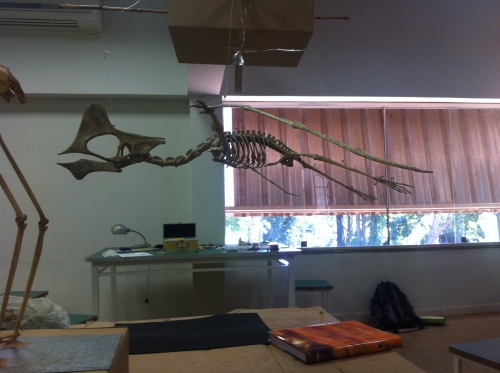

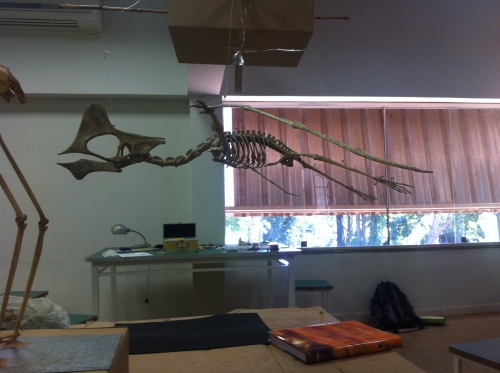

Finally assembling the Tapejara at the Peiropolis Dinosaur Museum. It will stay in this room (which contains several skeletons that are not yet on display) until it is installed. Here I hanged the body, head, a leg and a wing.

And this is the final result.

Hmmm… It might need some chiropractic therapy for that scoliosis.

Looks good, but the posture is still not right.

That’s not a good posture for the neck!

It should be facing down slightly. Like this.

Now it’s much better.

And that’s it! Now there is a Tapejara in the Peiropolis Museum. It will still receive a coating of matte varnish, and then it will be displayed in the main hall of the museum, near the big dinosaurs. If you ever go to Uberaba, check it out!

As in any project like this, there are some adjustments that can still be made, improvements in posture and eventual fixes that might have to be done in the future. If I have the opportunity to do so, I will review the replica next time I am in Uberaba. Some improvements that may be done very easily include 1) straightening the gastralia axis (it’s making a curved line), 2) reducing slightly the curvature of the back (it should be curved, but perhaps it was too much – that might be causing the curvature in the gastralia axis), and 3) removing sternal ribs connected to gastralia (or maybe simply trimming them).

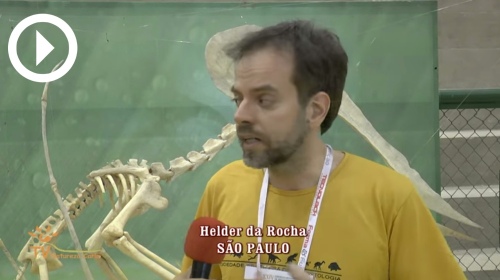

This was the Imaginary Pterosaur #7: Tapejara wellnhoferi, the first one I made for a museum. It was commissioned work and I started it two months ago, working on it about half of that time, traveling with it and working on it in different cities. Although I made all the bones by myself, I had help from many people. First of all I would like to thank the paleoartist Rodolfo Nogueira for introducing me to the director of the Peirópolis Cultural and Scientific Complex, Vicente Antunes, who had told him that he wished to have a pterosaur on display in the museum; the staff at the museum and UFTM, specially the researchers Thiago Marinho and Agustin Martinelli, who first contacted me and led the process that allowed me the opportunity to create this replica for the museum. Several other researchers helped me with photographic sources, articles and paleontological information: Hebert Bruno Campos, Felipe Pinheiro, and specially Brian Andres who gave me access to many photographs and measurements that were critical to the accuracy of this replica. Finally I must thank the family who hosted me in Uberaba: Alípio, Regis, Ludmila and Lucia (and their many cats) for their fantastic hospitality, for dedicating time and effort to make my stay as comfortable as possible, for driving me to Peiropolis and back (40km!) and even letting me occupy their kitchen table during three days, turning it into a pterosaur assembly lab!

Now I will stop making pterosaurs for about a month and a half because I will travel to Europe (Spain, Portugal, England and Russia). When I return, I will probably start Imaginary Pterosaur #8.

I will publish one more post on Tapejara with statistics (weight, dimensions) and links to pictures of all the parts.